Half a route in Shimshal

Pakistan - 2017

The porter was speaking fast and animatedly to our guide Karim. As the conversation went on, a small crease of concern crept across Karim’s face. When he spoke, his mouth beamed with his characteristic smile, but the uncertainty in his voice was distinctly noticeable,

“We lost a donkey. He is dead, he fell into the river.”

Two thoughts formed in our minds: firstly the image of a flailing creature plunging down the side of the hundred metre gorge, its walls so steep we didn’t see the river below for hours at a time. Secondly, we wondered which of our bags was on the donkey.

“It is the cooking tent. We lost the tent, and half of our fuel.”

We relaxed slightly, and then the morbid image in our minds shifted to include a fireball upon impact.

Within the hour, our jovial band of porters and donkeys had joined us at Purian Sar for lunch and it was clear that today’s gossip consisted of just one topic. At our camp the night before, we had drifted to sleep beneath the braying of a rather horny male donkey, pursuing his prize across the camp with limited success. It now transpired that earlier today he had spied the beautiful female ass on the switchback above him and unable to contain the urges that stirred inside, made straight for her up the scree. He died chasing what he loved.

“We lost a donkey. He is dead, he fell into the river.”

We were the British Shimshal Expedition 2017, a rather grand title for what would be better described as four friends on a climbing holiday. Similarly matched in ambition and inability, we were travelling to Shimshal in north-west Pakistan on the advice of Karim Hayat, a local climber and guide whom I had met in Yosemite nearly one year before. Unlike some of my previous travels in central Asia, most of my friends and family had at least heard of Pakistan, even if their knowledge was shockingly limited, confined mostly to vague associations with terrorism and the Taliban. Undeterred, Ross, Clay, Steve and I put these concerns aside and came here with one purpose, to attempt some new routes on a small clutch of unclimbed mountains in the Shimshal valley.

Approaching the site of our basecamp in the Gunj-e Tang valley involved a succession of transportation, each progressively less mechanised and more intimate with the environment than the last. From Islamabad we flew 45 minutes to Gilgit, soaring like birds past the fabled faces of Pakistan’s 8000m peaks which emerged just for a moment from a duvet of cloud to remind us of the heights to which we one day might aspire. From Gilgit we drove north towards Karimabad, pausing only when held up for an hour to admire the spectacle of the local police force’s efforts to clear the road for the president’s entourage. Like a who’s who of 20th Century weaponry, each policeman was armed in a different way; perhaps they had queued at the armoury that morning and been allocated equipment on a first come first served basis?

In Karimabad we changed vehicles, the much smaller, open-sided 4x4 providing no shielding from the realities of the road to Shimshal. Blasted horizontally across the cliffs, this single width track is just a few years old. It hugs a twisting, ancient waterway which shoots east towards Shimshal, welcoming visitors with a barrage of dust and buffeting made mercifully bearable by the beautiful views below. At every narrowing above the steep sided gorge I was thankful that I knew and trusted Karim to find us a driver and vehicle in a fit state to traverse this spectacular highway.

“We flew 45 minutes to Gilgit, soaring like birds past the fabled faces of Pakistan’s 8000m peaks which emerged just for a moment from a duvet of cloud to remind us of the heights to which we one day might aspire”

Shimshal was wonderful, a small oasis of tranquillity hidden high in the mountains near the Chinese border. Village life felt like a glimpse into 18th Century rural England, with only the juxtaposition of solar panels and scythes, or farmland and Facebook adverts, providing any hint of the influence of the modern world on the inhabitants’ way of life. We joined seemingly the entire male population in a high-altitude game of football where our excuses of clumsy approach shoes, a boulder strewn field and noticeable oxygen deficiency covered for our shockingly poor technique.

The next morning we hired eighteen porters and eight donkeys for the final stage of our journey; access to the mountain pastures beyond was possible only on foot. Our small procession threaded its way along the banks of the Pamir e-Tang River, the path no more than a delicate alignment of tree roots and boulders bonded magically to the sheer cliff walls. Irrespective of any climbing objectives, a trip to Shimshal for this hike would be a worthy objective in its own right.

And then finally, after three days and the loss of one donkey, we reached the mountains.

“Only the juxtaposition of solar panels and scythes, or farmland and Facebook adverts, providing any hint of the influence of the modern world on the inhabitants’ way of life”

Pakistan christened our new basecamp with a dump of fresh snow. I thought to myself how beautiful it would look on Instagram, whilst wishing out loud that more favourable conditions would soon arrive.

Along with Karim, who was really more friend than guide, we had retained the services of a cook and his assistant. Ensuring a plentiful supply of food that is both nutritious and tasty can be the crux for any expedition; with no time to shop for ourselves we had placed all our faith in Rahim and Sajad’s culinary sensibilities.

On the first morning of the approach trek Rahim passed us all a small lunch bag. It turned out, upon later inspection, to consist of a boiled potato, boiled egg and a handful of nuts. Ross and I sat together that lunchtime, slowly chewing our partially cooked potatoes and silently fearing for our diet and sanity over the coming weeks. This sort of beginning didn’t bode well.

We never quite understood if it had been a form of Pakistani culinary joke, but the change that followed couldn’t have been more dramatic. Every day, Rahim and Sajad delivered a steaming succession of stunning concoctions, brought to life from the flickering flames of our two ring gas hob on the floor of the mess tent: vegetable soups to start, gigantic dishes of rice and pasta, fresh melon, omelette and marmalade wraps, curries, breads and piles of french fries. Rahim was as good a cook as he was a boulderer and having burned us off all of our improvised boulder problems on the approach trek that was quite a compliment. By the time we got to day four and he pulled out a great crème caramel for dessert he was definitely showing off.

“By the time we got to day four and he pulled out a great crème caramel for dessert he was definitely showing off”

Two weeks previously I had guided a friend up Mont Blanc, but any acclimatisation gained from that ascent had most certainly now abandoned me. Indeed, the crumbling rock ridge besides the Grand Couloir in Chamonix is grossly inadequate preparation for the disastrous moraine that welcomes and then ensnares any climber wishing to explore the depths of the glaciated regions of central Asia. Ross, Karim and I worked hard to earn the right to place our advanced basecamp atop a cosy plateau at the base of the glacier. Below, caravan sized pieces of moraine wished nothing more than to tumble down the valley beneath, cheese in a mousetrap awaiting the wayward foot of a climber. But above, beyond a small band of seracs, a long flat glacier, and a faint wisp of cloud, it lay. An isolated, regal, 6000m peak, and our objective for the expedition.

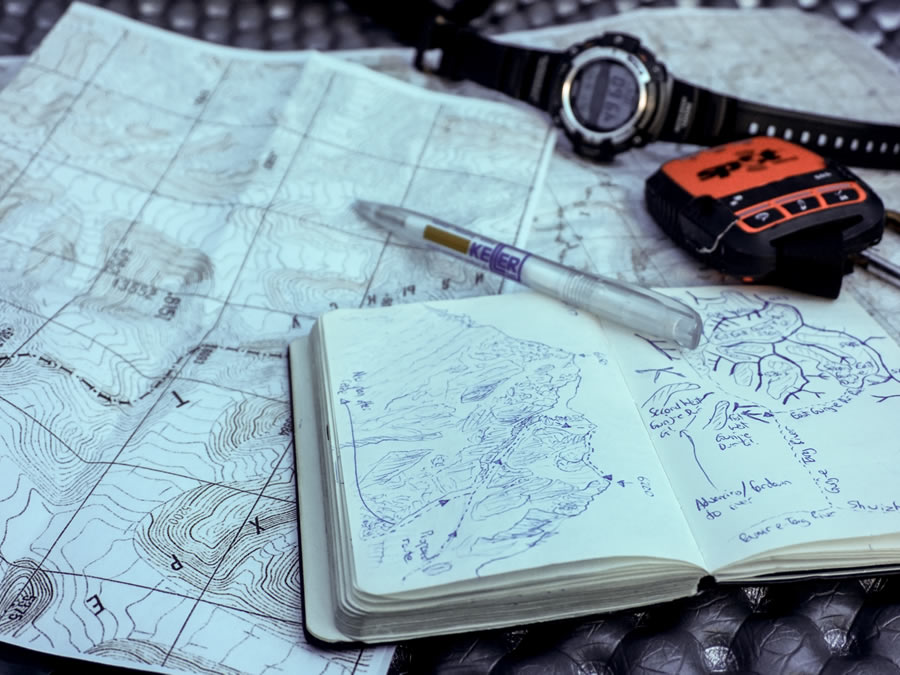

Ross had first spied the peak in Google Earth some nine months before. In basecamp we had briefly considered joining Steve and Clay in a neighbouring valley where they were keen to climb, but after seeing our peak for the first time all considerations of alternative objectives fell away. It was the perfect combination of visual prominence, technical challenge and objective safety: a holy trinity of excitement that we wouldn’t dare have contemplated from our bedrooms back in England. As planned our expedition split into two smaller parties and after eight days on the move we had both established our respective advanced camps. All eyes were on the prizes above.

For most expeditions to Asia, those first eight days could easily be eaten up in bureaucracy and sight-seeing in a local town. Not us, sadly. Unable to afford the luxury of taking extended holidays from work, we were nonetheless unwilling to settle for a more conventional destination. The compromise was that our expedition was to be crammed into 19 days and already a third of that had been taken up simply getting to basecamp. Karim’s dry wit reminded us of this from time to time, asking with a smile whether we felt the British Trekking Expedition was a success or not. The coming week was to be a race to climb, descend and return in time for our flights back to the office the following Monday.

“It was the perfect combination of visual prominence, technical challenge and objective safety: a holy trinity of excitement that we wouldn’t dare have contemplated from our bedrooms back in England”

At midnight on the morning of 5th September, Ross, Karim and I rose to the silence of a cloudless night. Crampons crunched comfortingly on frozen snow and silver moonlight glinted like yarn across the peaks behind us, a reminder of how perfectly the weather had fallen in place with our plans. Our slow march towards the summit began.

Roped together we hopped across crevasses, following with ease tracks laid down the previous day. Before long an extensive bank of glacial ice lay above us. Our original intention had been to climb a route on the spectacular north face of the mountain, but as the realities of our tight timeline had hit home we’d switched our plans to the biggest line of weakness: a direct route up the middle of the south face. In high spirits and feeling confident, I had little idea quite how short a day’s climbing it was to prove for me.

Absorbed in my own thoughts, I progressed silently up the slope behind the others. There is a rhythmic tranquillity that comes with ascending easy, Scottish grade I terrain, particularly on a windless morning just as dawn summons the courage to strike. A harmony of colours were spreading gracefully across the horizon like a heavenly parrot, stroking wings of purples, oranges and yellows across a thousand distant summits. In that moment I felt perhaps the happiest I’d ever been in the mountains. It came, therefore, as something of a surprise to find myself violently retching just moments later, slumped over my axe, knees to the ice.

We continued on, trying to ignore it, but continued exertion wasn’t proving the antidote I had hoped for. I was quite clearly not well, most likely succumbing to the altitude but still with another 500m of ascent left to complete. We deliberated for nearly an hour, for although deciding what I had to do took less than a minute, coming to terms with it was far harder. Leaving the others to forge ahead, I descended alone and for the first time in the mountains found myself crying as I did. Dreams, plans and excitement rolled slowly off my cheeks, dripping into cracks in the ice beneath me. Half way up our first and only objective, my time climbing in Pakistan was over.

“A harmony of colours were spreading gracefully across the horizon like a heavenly parrot, stroking wings of purples, oranges and yellows across a thousand distant summits”

Ross and Karim summited the 6015m peak that afternoon. Stretched out ahead of them was a knife-edge ridge of sugary snow which looked spectacular but was completely incompatible with a long career as an alpinist. They made a wise choice and descended on abalakov abseils the hanging glacier that had formed the second half of the climb. Ecstatic and exhausted, they stumbled back into camp just before sunset to relieve me from John Grisham. “This route is too long, it needs a camp 1,” declared Karim, and promptly fell asleep.

In the adjacent valley, Steve and Clay had also seen success, climbing a new route the previous day on a peak attempted by a Japanese team in 2001. They had ploughed a long course through deep snow, thankful as the thick clouds rolled in that it presented only a few technical difficulties. “I only made Clay rope up because I didn’t want to carry the rope anymore,” grinned Steve to us back in camp.

Climbing complete, only a heavy, painful load-carry separated us all from another of Rahim and Sajad’s signature dishes. Rahim hadn’t wasted any time in our absence, claiming most of our basecamp boulder problems for himself by building great towering cairns on their rocky summits. Swap his soleless shoes for some B3s and who knows what he could achieve. Karim promised us a treat of the rare snow peacock for dinner; our gullible minds were clearly addled after our brief time in the mountains for the meat looked suspiciously like chicken. It was time to go home.

Our return to Shimshal three days later coincided with the arrival of solar lighting to the town. To celebrate, it was quickly decided that for some reason I should commission a new solar lamp post for the village elders in front of the entire town. They politely listened to my ramshackle speech and didn’t laugh at any of my jokes.

So far from home, the Ismaili Muslim people of the region had time and again shown us such wonderful hospitality. When our short flight to Islamabad was cancelled, Karim and our driver thought nothing of making a spontaneous, fourteen hour drive back to the capital so we could all catch our connections home. The Foreign Office advise against all travel along the Karakorum Highway but our traverse of this stunning mountain road passed without incident, save for one (major) detour when our paperwork proved insufficient for us to take a shortcut through the state of Kashmir. As we drew close to Islamabad I motioned casually to the tall towers on the horizon, eager to show off my new-found knowledge of Islamic culture,

“You can tell which are Shia or Sunni mosques by the number of towers,” I began.

“Yes, sure,” countered Karim, “but that’s a Chinese brick factory”.

Clearly I still had much to learn. I may have only managed half a route in Shimshal, but I hope one day I can return to climb at least half a route more.

“Karim promised us a treat of the rare snow peacock for dinner; our gullible minds were clearly addled after our brief time in the mountains for the meat looked suspiciously like chicken.”